Icons That “Crossed” the Ocean: How Ukrainian Artist’s Style Connected Lviv and Curitiba

In Curitiba, Brazil, home to around 600,000 descendants of Ukrainian immigrants from Galicia now live, the Ukrainian language and prayers are still heard. There is a square called “Ukraine,” whose cobblestones are laid out in patterns reminiscent of embroidered shirts, and the Basilian parish of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, with its icons, resembles the church of the same name in Lviv. What connects these two shrines — more on that below.

Curitiba, the capital of the state of Paraná, became one of the main centers of Ukrainians in Brazil at the end of the 19th century. At that time, thousands of peasants from Galicia came here in search of a better life. Today, most Ukrainians in Brazil are fourth or fifth generation descendants of the first settlers.

The spiritual center of the community is the Curitiba Metropolia of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, headed by Metropolitan Volodymyr Kovbych.

“Our rites helped preserve Ukrainian culture here,” says the bishop. “Even the ‘Latins’ recognize that it was this rite that prevented Ukrainians from assimilating, because along with the Liturgy, we preserved our language and customs.”

There are icons by Ukrainian iconographer Sviatoslav Vladyka, a native of Ivano-Frankivsk, at the Parish of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. His works can be found in Lviv, Mukachevo, Ternopil, Chernivtsi, and even as far away as Brazil. The Basilian church in Curitiba is remarkably similar to the one in Lviv: the icons of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and St. Nicholas are almost identical.

“It seems as if I have come to my home parish,” says Taras Babenchuk, a journalist at Zhyve TV, who visited the community during a working visit.

Sviatoslav Vladyka began painting this iconostasis on the 50th anniversary of the church, but did not manage to complete the work. Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the artist has been defending his homeland in the ranks of the Armed Forces.

“Sviatoslav, if you see this video, I salute you. I wish us all victory. Thank you for setting aside your paintbrush to defend your homeland. I hope you can return to your icon painting as soon as possible,” said Taras Babenchuk.

The parish does not give up hope that once the war ends, the craftsman from Ukraine will return here to continue painting the church.

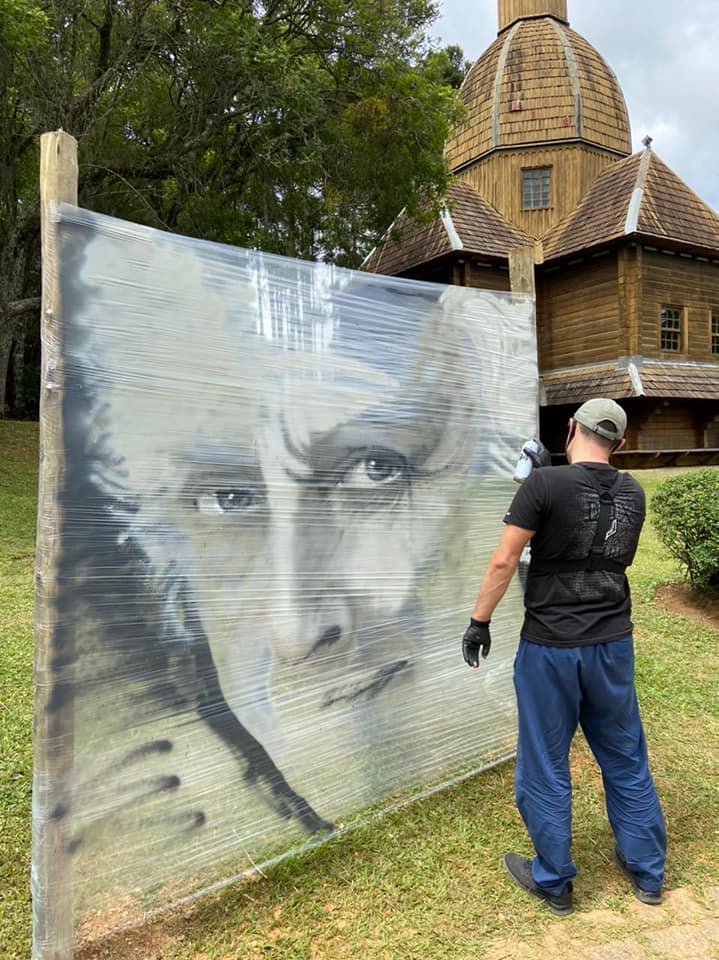

Icons by Sviatoslav Vladyka can also be seen at the Ukrainian Immigration Memorial in Tingui Park, an open-air museum that tells the story of Ukrainians in Brazil. Here, a Ukrainian hut, a bell tower, a monument to the victims of the Holodomor, and the wooden Church of St. Michael — an exact replica of one of the oldest Ukrainian churches in Brazil — have been recreated. Inside, there is an exhibition of pysanky, embroidery, icons, and portraits of Taras Shevchenko and poet Olha Kolodiy, also created by Sviatoslav Vladyka.

“It is incredible to see a memorial dedicated to immigrants from Ukraine so far away, in Curitiba,” says Dr. Vitaliy Tokar, Doctor of Canon Law. “It tells our story, our hardships, and our fortitude. Hundreds of Brazilians come to this unique place and, looking at the memorial, discover our culture and the path that Ukrainians have traveled, and understand that wherever we are, we always remain Ukrainians, demonstrating our love for our homeland.”

For more about Ukrainians in Curitiba, spiritual life, local monastic communities, seminary gardens with tangerines and bananas, as well as capybaras peacefully walking in the park, see the report on Zhyve TV.

The UGCC Department for Information