Inside the UGCC Humanitarian Headquarters: How it Works at the Saltivka Cathedral in Kharkiv

Mid-April in Kharkiv is hot and dry. This is especially palpable on the square in front of the central railway station. In Kyiv, the war reminds us of itself with air raid sirens and the sounds of air defense. In Kharkiv, at first glance, it seems the same. However, after spending half a day in the city, a naive Kyivan realizes that the alarm is constant, and the loud “bangs” you hear from time to time are not from air defense, but from Russian missiles exploding.

After such strikes, public transportation stops, and residents are forced to do without electricity, mobile phone service, and the Internet for weeks. Moreover, there are not many citizens in Kharkiv. In the third year of the full-scale war, the sprawling city of one million inhabitants with its wide streets, high-rise buildings and private sectors looks deserted.

Wednesday, 1:00 PM

“Oh, no! Now many people have returned, it’s more bustling — there are cars, even the police stop us,” says Fr. Serhiy Tymchuk, driving a minivan on the way to St. Nicholas the Wonderworker Cathedral. “Two years ago, on April 22, I was traveling to Kharkiv on an empty train. There were only two passengers along with me. A car passed by our cathedral in Saltivka maybe once every few hours. It was as quiet as a cemetery.”

Today, the UGCC Cathedral in Saltivka (the largest residential area in Ukraine) can hardly be called deserted. In the backyard, behind the huge under-construction church, people are bustling around — a humanitarian aid truck has just arrived. “From Rome, from St. Sophia Cathedral,” explains Fr. Serhiy. People are fussing around the truck, men are unloading boxes: pasta, medicine, cookies, children’s clothes. Women are sorting clothes. Bishop Vasyl Tuchapets is attentively observing the process, answering questions from the volunteers, and simultaneously recording a video with gratitude for the parish from Rome that sent the aid.

— We have a bishop who comes from the common people, says one of the volunteers as she sorts through clothes. — That’s right because the Church should always be with the people. Our leader is God, and our bishop is top notch! (raises a thumb up, gestures “excellent”).

10 years ago, on April 2, 2014, the year when Crimea was annexed and the war in Donbas began, the Kharkiv Exarchate was proclaimed. In May of the same year, Father Vasyl Tuchapets became a bishop, and in June he was enthroned as the Kharkiv Exarch.

“In 2014, Kharkiv greeted me like a secularized Soviet city-not exactly friendly.”

“But with each passing year, Kharkiv and I became accustomed to each other—or rather, I became accustomed, and it gradually changed in mood, shedding the shackles of Russian propaganda,” says Bishop Vasyl.

“In 2014, Galicians who had been working in Kharkiv formed the foundation of the parish. Over the 10 years of my stay here, locals, Kharkiv residents, who consciously chose our Church, gradually appeared. And now, especially after the outbreak of a full-scale war, the parish is almost 100 % filled with locals. The war changed Kharkiv residents; they began to identify themselves as Ukrainians. Furthermore, while they may not have become Christians or started attending the Liturgy every Sunday, they have definitely developed a commitment to the Church.”

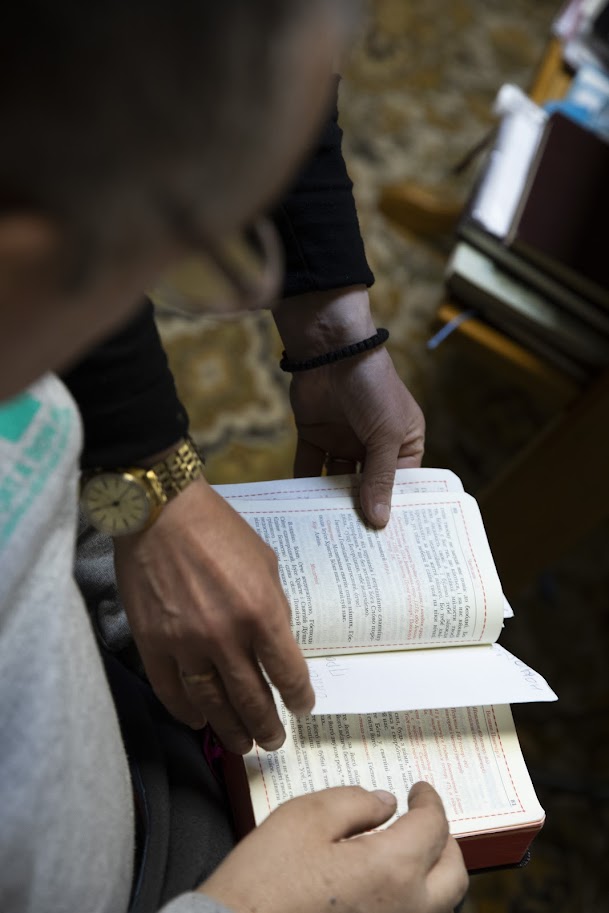

Several times a week, Fr. Serhiy conducts catechism classes for children. Since schools and kindergartens in Kharkiv do not work, even on weekdays the church is filled with children.

Bishop Vasyl recalls the outbreak of the great war in Kharkiv as if it were a scene from a movie about the end of the world: he woke up at 5 a.m. to rocket attacks, it was dark; he looked out the window and saw the flames of fires. The television was not working—there was a news ticker running at the bottom of the screen, announcing that the war had begun.

“A security guard from the church called and said, ‘It’s war! Please come, because I’m leaving!’ — the bishop says. — And I have a Basilian monk visiting me, who came to see Kharkiv for a few days. It’s 6 o’clock in the morning, and we’re driving to church together, and I see people with suitcases and bags walking toward us to the train station in the center. There are huge lines at gas stations. There is no transportation. No electricity, no communication. I remember standing in the church yard, and a young man walks by and addresses us: ‘Look what these brutes are doing!’” (he pauses).

“I remember on Maundy Thursday, April 21, 2022, the Russians fired cluster shells at Kharkiv. In the evening, I was talking on the phone in the kitchen and heard an explosion (the shell exploded in the air and the shrapnel fell into our yard). One of them landed on the carpet in my bedroom,” Bishop Vasyl shares his memories.

In the spring of 2022, during the fighting on the Kharkiv Ring Road, the northern part of Saltivka suffered the most. Bishop Vasyl recounts how more than 1,500 people were hiding at the Heroes of Labor metro station during those battles.

“We brought blankets there several times. It was stuffy and cramped. People described how they would walk through the tunnel along the tracks to the neighboring metro station every Saturday to bathe. A fitness club with showers and toilets adjacent to the station was open.”

Today, the residential area destroyed by shelling remains uninhabitable. Several houses have been restored, while those that cannot be restored are being dismantled. Broken windows are covered with plywood, and the blackened remnants of air conditioners barely cling to the charred facades. The air smells of construction dust. Two pigeons walk solemnly between the daffodil bushes—apparently, someone’s caring hand planted the flowers in a place where no one has lived for two years.

Wednesday, 4:45 PM

After returning from northern Saltivka, Bishop Vasyl meets a mustachioed man in a wheelchair (“Mr. Mykola, our chief baritone”) and a young woman in a headscarf in the churchyard.

— “Katyusha, how are you?” he asks.

— “I let the soldiers go, gave them condensed milk, fresh bread, rice…” Katya reports.

Her arms are at her sides, hostess-like, with a prayer book in her hand. Together with her husband, Katia cares for the church. She also sings at the services. Vespers begins at 5 p.m. every day.

Wednesday, 7:00 PM

“I’m expecting you tomorrow at 7:30 for Matins. Don’t oversleep!” Katya says so decisively that I don’t dare to oversleep.

The driver of the truck, which has been unloaded for the day, approaches Bishop Vasyl to say goodbye. He honks his horn several times on the way out of the grounds. Everything is ready for tomorrow’s distribution of humanitarian aid.

The story of the large headquarter began with a single truck that accidentally arrived in Kharkiv during the third week of the full-scale war. Bishop Vasyl recalls:

“Father Volodymyr, a chaplain from Skole, called me. He asked if I needed help. I answered: ‘Yes, please do.’ It was Saturday evening. During the curfew, we unloaded it, and on Sunday after the Liturgy we started distributing it. That’s how it all started.”

Thursday, 7:45 AM

The next morning, a line slowly forms at the church gate. Over two years of work, the volunteers have developed a well-established procedure. A few hours later, around 11 o’clock, they start letting people in and giving them food according to their coupons. There are also separate lines for people with disabilities and parents with small children.

“What hasn’t happened here! Children were exchanged, strollers were swapped, people fought for a place in line, and it almost ended in stabbings!” says Valera, one of the volunteers, a Kharkiv resident.

People are now accustomed to discipline, he says. But there are also tricksters who try to queue twice to get two coupons. While we keep the conversation going, Valera watches the line, looks closely at the woman in black, nods to a friend standing twenty meters away. This means: keep your eyes open.

— Everything has to be fair, — says Valera.

The Humanitarian Headquarter operates thanks to the work of nearly a hundred volunteers, all of whom are locals. Initially, they came to receive the aid themselves, and later stayed to help distribute it.

— It was quite an attack, wasn’t it?

Yaroslav (or simply Slavik, as he is known here), a charismatic, boisterous man of about 55, stands out among Russian-speaking Kharkiv residents for his distinctly Galician accent. Originally from the Lviv region, he came to Kharkiv 34 years ago after graduating from college and being assigned to work here. He stayed here with his wife.

— Later, there will be wheelchair users, mothers with children, and “veterans of the Battle of Borodino” (laughs). I mean those who are over seventy,” Slavik explains, waving his arms restlessly (How can anyone have that much energy?) But you can rest until half past eleven. You should get some shade (he nods and wipes the sweat from his forehead), because you can fry in the sun.

In the shade, near the point of invincibility, where there are taps with drinking water, two women are filling ten-liter plastic jugs. A barely audible “Lord, have mercy” drifts into the street as the Liturgy continues in the lower church.

— They say they hit CHP-3 this morning, says one woman.

— But it hasn’t been working for a long time, replies the other.

— And moles have dug up my entire garden, the first woman recalls after a pause.

— Oh, no way! What a pest, the second woman sympathizes.

They both load jugs with water onto metal hand trolleys and, after a quiet conversation about the weather, the garden, high blood pressure, and power outages, head home.

Thursday, 11 AM

The noise in the yard is getting louder.

“Initially, we distributed food every day, then three times a week, and now only once,” says the bishop. “We see that despite everything, people are doing better. Now, for some reason, there are the longest lines for medicines — people ask for blood pressure medicine, painkillers, and cold medicines.”

We bypass the queue and enter a tent with medicines that resembles a field pharmacy. Three cheerful women start discussing the organization of their territory. A neonatologist with 52 years of experience, a lecturer at the National University of Pharmacy, and a pharmacist — the field humanitarian pharmacy is staffed by professionals with vast experience.

“Here we have iron supplements, B vitamins, cough suppressants, paracetamol…” says the confident blonde volunteer, “All the medicines are signed, with explanations of what to take, when and how to take them.

After checking the organization, Bishop Vasyl gives the command to start letting people in. The line begins to move.

Next to the pharmacy is a tent with baby food and formula. A long line of mothers with strollers and children in their arms stretches toward it.

People are constantly approaching Bishop Vasyl with questions, asking for his blessing to receive assistance, and showing him their documents.

“People come with very different requests. For example, on Sunday, a woman in her 90s approached me and said, ‘Your Eminence, I have not slept a wink all night. Pray that I get some sleep,’” Bishop Vasyl smiles.

“People are most in need of food,” the bishop admits, “but unfortunately, we are receiving less and less food with each delivery…”

Thursday, 1 PM

As the afternoon wore on, the noise in the churchyard slowly quieted down. Everyone who needed help received it. Volunteers are having lunch at the Point of Invincibility. Several explosions are heard nearby. Half a minute later, a siren went off, but no one pays attention to it. Halyna, a young woman in work clothes with gardening tools in her hands, asks if we, Kyivans, liked it in Kharkiv, tells us about the sudden warming, about the flowers she plans to plant in the small garden near the church, asks if we liked the jam pie she served us yesterday. She tries to speak Ukrainian.

“Explosions? No, it’s not scary,” she waves his hand. “Scary is when you cook the last packet of pasta for your children (I have four) and know that there is nothing else”, she pauses for a moment, smiles and heads to the garden.

It’s a warm afternoon. Shelling can be heard in the distance. The thermal power plant which was hit in the morning is still smoking. Volunteers are having lunch at the Point of Invincibility. Halyna is planting flowers in the garden near the church.

Text: Marta Synovitska

Photo: Oleksandr Savransky

The UGCC Department for Information